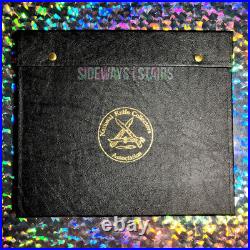

Check out my other new & used items>>>>>> HERE! A very rare, vintage NKCA branded accessory. NATIONAL KNIFE COLLECTORS ASSOCIATION POCKET KNIFE STORAGE CASE. Holds 24 pocket knives! This vintage National Knife Collectors Association pocket knife collection holder is perfect for storing NKCA club exclusive knives. There’s enough space to easily and safely store 24 pocket/ folding knives. The exterior of the case is made of a vinyl/ faux leather that features a classic textured finish. On the front of the storage case is a metallic gold colored NKCA logo that coordinates with the bright brass snaps. The inside is lined with dark red velour and includes additional fold over fabric for protecting your knives from dust and scratching. This knife folder is ideal for transporting a pocket knife collection as it is lightweight yet sturdy. Stores easily in a drawer and looks great stored on a shelf. 12-11/16″ (L) x 11″ (W) x 1-1/4 (H). New condition; new old stock. This vintage case has never been used, it is in excellent shape. THANK YOU FOR LOOKING. ALL PHOTOS AND TEXT ARE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OF SIDEWAYS STAIRS CO. A pocketknife is a foldable knife with one or more blades that fold into the handle. It is also known as a jackknife (jack-knife) or a penknife, though a penknife may also be a specific kind of pocketknife. [1][2] A typical blade length is 5 to 15 centimetres (2 to 6 in). [3] Pocketknives are versatile tools, and may be used for anything from opening an envelope, to cutting twine, slicing a piece of fruit to a means of self-defense… History Roman pocketknife: original with a modern reconstruction beside it The earliest known pocketknives date to at least the early Iron Age. A pocketknife with a bone handle was found at the Hallstatt Culture type site in Austria, dating to around 600-500 BCE. [5] Iberian folding-blade knives made by indigenous artisans and craftsmen and dating to the pre-Roman era have been found in Spain. Many folding knives from the Viking era have been found. They carried some friction binders, but more often they seem to have used folding knives that used a closure to keep the blade open. Peasant knife Smaller Opinels are a type of peasant knife The peasant knife, farmer knife, or penny knife is the original and most basic design of a folding pocketknife, using a simple pivoted blade that folds in and out of the handle freely, without a backspring, slipjoint, or blade locking mechanism. [6] The first peasant knives date to the pre-Roman era, but were not widely distributed nor affordable by most people until the advent of limited production of such knives in cutlery centers such as Sheffield, England commencing around 1650, [7] with large-scale production starting around the year 1700 with models such as Fuller’s Penny Knife and the Wharncliffe Knife. [8] Some peasant knives used a bolster or tensioning screw at the blade to apply friction to the blade tang in order to keep the blade in the open position. 2-5 Opinel knives are an example of the peasant knife. [6] The knife’s low cost made it a favorite of small farmers, herdsmen, and gardeners in Europe and the Americas during the late 19th and early 20th century. Slip joint knife Main article: Slipjoint Most pocketknives for light duty are slipjoints. This means that the blade does not lock but, once opened, is held in place by tension from a flat bar or leaf-type backspring that allows the blade to fold if a certain amount of pressure is applied. [6] The first spring-back knives were developed around 1660 in England, [9] but were not widely available until the Industrial Revolution and development of machinery capable of mass production. Many locking knives have only one blade that is as large as can be fitted into the handle, because the locking mechanism relies on a spring-loaded latch built into the spine or frame of the handle to lock it and it is difficult to build in multiple levers, one for each blade. Slipjoints tend to be smaller than other typical pocketknives. Some popular patterns of slipjoint knives include: Pattern Description Image Barlow The Barlow knife has a characteristically long bolster, an elongated oval handle, and one or two blades. [10] It is assumed to have been named after its inventor, although there is some dispute as to which Barlow this actually was. First produced in Sheffield, England, the Barlow knife became popular in America in beginning of the nineteenth century. [11][12] Case Damascus Barlow Knife Camper or Scout The traditional camper or scout knife has four tools: a large drop point blade along with a can opener, combination cap lifter/slotted screwdriver, and an awl or punch. Many other combinations of large and small drop point blades, a Phillips-head screwdriver, saw, etc. Are also considered camper/scout knives. Victorinox Soldier, a Camper or Scout pattern pocketknife Canoe The canoe knife is shaped somewhat like a native American canoe and typically has two drop-point blades. A canoe knife Congress The congress knife has a convex front with a straight or shallow concave back. It usually carries four blades. A congress knife Elephant’s toenail The elephant’s toenail is a large design similar to the sunfish but usually tapers on one end giving it the “elephant’s toenail” shape. These knives, like the sunfish, usually have two wide blades. Toothpick Elongated knife, with a single narrow clip point blade. Handle has bolsters at both ends, and is turned up or tapered on the opposite end of the blade. Variations include oversized versions called Arkansas or Texas Toothpicks, and miniaturized version, called a Baby Toothpick. A Toothpick knife Lady Leg Drop point blade paired with a clip point blade, with a handle shaped like a lower leg with a high-heeled shoe, which forms a functional bottle opener. Marlin Spike A single sheepsfoot or hawkbill blade, with a large sailor’s spike, to assist in untangling knots or unravelling rope for splicing on the opposing side. Peanut A smaller knife with a clip point and drop point from the same end, double bolsters on a slightly wavy handle. Case “Peanut” model with clip and spey blades Dog Bone Double bolstered handle with a blade opening from each end. The blade is symmetrical, with roughly parallel sides. Hawkbill Technically a blade type (resembling a hawk’s bill, with a concave sharpened edge and a dull convex edge), but also a traditional single-bladed slip joint knife with a single bolster on the blade end, and a teardrop-shaped handle. Dog Leg A double bolstered handle with a significant cant, resembling the shape of a dog’s hind leg. Can have one or two blades that open from the same end. Sow Belly Has a handle with deeply bowed “belly”, similar to a stockman, but more pronounced. It may have a single clip point blade, or a sheepsfoot and clip point blade opposite a shorter spey blade. Case Sow Belly with three blades Muskrat Two narrow clip point blades, one from each end, with double bolsters. Melon Tester Single long and narrow drop point blade, used for taking a sample from watermelon. Cotton Sampler Shorter knife, bolster on the blade end only, and a single scalpel-style blade. Penknife The penknife was originally intended to sharpen quill pens, but continues to be used because of its suitability for fine or delicate work. A penknife generally has one or two pen blades, and does not interfere with the appearance of dress clothes when carried in the pocket. Buck Two-Bladed Pen Knife. Primary Blade Two Inches Sodbuster The sodbuster or Hippekniep or Notschlachtmesser (sometimes also called the Farmer) has a simple handle with no bolster and only one blade. It is an economic design, usually with wood or celluloid scales, lacking metal bolsters. Herder Hippekniep Stockman The stockman has a clip, a sheep’s foot and a spey blade. They are usually middle-sized. There are straight handled and sowbelly versions. A medium stockman knife Sunfish The sunfish is a large design with a straight handle and two bolsters. The blades are usually short less than 3 inches (76 mm), but both the handle and blades are very wide. Sunfish knives usually have two blades. A small sunfish knife Trapper The trapper is larger knife with a clip and a spey blade. The blades are usually hinged at the same end (that is to say, it is a jack-knife). A Case Trapper knife with stag scales Whittler The whittler is a type of pen knife with three blades, the master blade bearing on two springs. [13] Multi-tool knives Soldatenmesser 08, the multi-tool knife issued to the Swiss Armed Forces since 2008 Main article: Multi-tool Multi-tool knives formerly consisted of variations on the American camper style or the Swiss Army knives manufactured by Victorinox and Wenger. However, the concept of a multitool knife has undergone a revolution thanks in part to an avalanche of new styles, sizes, and tool presentation concepts. These new varieties often incorporate a pair of pliers and other tools in conjunction with one or more knife blade styles, either locking or nonlocking. Multitool knives often have more than one blade, including an assortment of knife blade edges (serrated, plain, saws) as well as a selection of other tools such as bottle openers, corkscrews, and scissors. A large tool selection is the signature of the Swiss Army Knife. Similar to the Swiss Army knife is the German Army knife, with two blades opening from each side and featuring hard plastic grips and aluminum liners. Military utility knife (MIL-K-818), issued by the United States Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, was made for many years by the Camillus Cutlery Company and Imperial Schrade as well as many other companies. It was originally produced with carbon steel blades and brass liners (both vulnerable to corrosion), but with the onset of the Vietnam War was modified to incorporate all-stainless steel construction. Military utility knife has textured stainless grips and four stainless blades/tools opening on both sides in the camper or scout pattern and has an extremely large clevis or bail. Miscellaneous designs Another style of folding, non-locking knife is the friction-folder. These use simple friction between the blade and scales to hold the blade in place once opened; an example is the Japanese higonokami. An electrician’s knife typically has a locking screwdriver blade but a non-locking knife blade. The two-blade Camillus Electrician’s knife (the US military version is known as a TL-29) was the inspiration for the development of the linerlock. It is designed to be carried in a wallet along with regular credit cards. A ballpoint pen knife is generally a pen with a concealed knife inside, which can be used as a letter opener or as a self-defense weapon. Lock-blade knives Medium-sized lockback knife with deer-antler grips, nickel-silver bolsters and brass liners Knives with locking blades, often referred to as lock-blade knives or clasp knives, have a locking mechanism that locks the blade into its fully opened position. This lock must be released in a distinct action before the knife can be folded. The lock-blade knife improves safety by preventing accidental blade closure while cutting. It is this locking blade feature that differentiates the lock-blade knife from either the peasant knife or the slipjoint spring-back knife. Locking knives also tend to be larger: it is easier to fit a lock into a larger frame, and larger knives are more likely to be used for more forceful kinds of work. The cost of a locking mechanism is also proportionally less than it would be on a smaller, and generally cheaper, knife. Lock-blade knives have been dated to the 15th century. In Spain, one early lock-blade design was the Andalusian clasp knife popularly referred to as the navaja. [16] Opinel knives use a twist lock, consisting of a metal ferrule or barrel ring that is rotated to lock the blade either open or closed. In the late 20th century lock-blade pocketknives were popularized and marketed on a wider scale. Companies such as Buck Knives, Camillus, Case, and Gerber, created a wide range of products with locks of various types. The most popular form, the lockback knife, was popularized by Buck Knives in the 1960s, so much that the eponymous term “buck knife” was used to refer to lockback knives that were not manufactured by Buck. The lockback’s blade locking mechanism is a refinement of the slipjoint design; both use a strong backspring located along the back of the knife handle. However, the lockback design incorporates a hook or lug on the backspring, which snaps into a corresponding notch on the blade’s heel when the blade is fully opened, locking the blade into position. [17] Closing the blade requires the user to apply pressure to the spring-loaded bar located towards the rear of the knife handle to disengage the hook from the notch and thus release the blade. [18] The Walker Linerlock, invented by knifemaker Michael Walker, and the framelock came to prominence in the 1980s. In both designs the liner inside the knife is spring-loaded to engage the rear of the blade when open and thus hold it in place. [18] In the case of the framelock, the liner is the handle, itself. The Swiss Army knife product range has adopted dual linerlocks on their 111 mm models. Some models feature additional “positive” locks, which essentially ensure that the blade cannot close accidentally. CRKT has patented an “Auto-LAWKS” device, which features a second sliding switch on the hilt. It can operate as any linerlock knife if so desired, but if the user slides the second control up after opening, it places a wedge between the linerlock and the frame, preventing the lock from disengaging until the second device is disabled. Tactical folding knife Buck’s original lockback knife was originally marketed as a “folding hunting knife” and while it became popular with sportsmen, it saw use with military personnel as it could perform a variety of tasks. Custom knife makers began making similar knives, in particular was knifemaker Bob Terzuola. Terzuola is credited with coining the phrase “Tactical Folder”. [19] In the early 1990s, tactical folding knives became popular in the U. [20] The trend began with custom knifemakers such as Bob Terzuola, Michael Walker, Allen Elishewitz, Mel Pardue, Ernest Emerson, Ken Onion, Chris Reeve, Rick Hinderer, Warren Thomas, and Warren Osbourne. [21] These knives were most commonly built as linerlocks. Blade lengths varied from 3 to 12 inches (76 to 305 mm), but the most typical models never exceeded 4 inches (100 mm) in blade length for legal reasons in most US jurisdictions. [22] In response to the demand for these knives, production companies offered mass-produced tactical folding knives. Companies such as Benchmade, Kershaw Knives, Buck Knives, Gerber, CRKT, Spyderco and Cold Steel collaborated with tactical knifemakers; in some cases retaining them as full-time designers. [23] Tactical knifemakers such as Ernest Emerson and Chris Reeve went so far as to open their own mass-production factories. [24] There has been criticism against the notion of a “Tactical Folding Knife” when employed as a weapon instead of a utility tool. Students of knife fighting point out that any locking mechanism can fail and that a folding knife regardless of lock strength can never be as reliable as a fixed-blade combat knife. Lynn Thompson, martial artist and CEO of Cold Steel pointed out in an article in Black Belt magazine that most tactical folding knives are too short to be of use in a knife fight and that even though he manufactures, sells, and carries a tactical folder, it is not ideal for fighting. [25] Of course the idea that sells tactical knives (beyond the plain appeal of them) is that it is better to have a knife that is not ideal than to not have your ideal combat knife because it was too large to carry with you. While a 10-inch fixed-blade Bowie knife might be far more ideal for combat, it is not practical – or legal – for many people to carry one around with them on their belt all the time, and few people leave the house expecting or planning to get into a knife fight that day[citation needed]. Benchmade Bedlam auto-knife Benchmade 4300 CLA Composite Lite Auto. Auto knife push button operation with side mounted safety, reversible clip. Length 7.85- inches Blade length 3.4 inches. Other features Traditional folding knives are opened using nail-nicks, or slots where the user’s fingernail would enter to pull the blade out of the handle. This became somewhat cumbersome and required use of two hands, so there were innovations to remedy that. The thumb-stud, a small stud on the blade that allows for one-handed opening, led the way for more innovations. One of these being the thumb hole: a Spyderco patent where the user presses the pad of the thumb against a hole and opens the blade by rotating the thumb similarly to using the thumb-stud. [23] Another innovation of Sal Glesser, Spyderco founder, was the clip system, which he named a “Clip-it”. Clips are usually metal or plastic and similar to the clips found on pens except thicker. Clips allow the knife to be easily accessible, while keeping it lint-free and unscathed by pocket items such as coins. Assisted opening systems have been pioneered by makers like Ken Onion with his “Speed-Safe” mechanism and Ernest Emerson’s Wave system, where a hook catches the user’s pocket upon removal and the blade is opened during a draw. [18] One of the first one handed devices was the automatic spring release, also known as a switchblade. An innovation to pocketknives made possible by the thumb-stud is the replaceable blade insert developed in 1999 by Steven Overholt U. 6,574,868, originally marketed by TigerSharp Technologies and as of 2007 by Clauss. Some systems are somewhat between assisted opening and the normal thumb stud. CRKT knives designed by Harold “Kit” Carson often incorporate a “Carson Flipper”, which is a small protrusion on the rear of the base of the blade such that it protrudes out the obverse side of the handle (when closed). By using an index finger and a very slight snapping of the wrist, the knife opens very quickly, appearing to operate like a spring assisted knife. When opened, the protrusion is between the base of the sharp blade and the user’s index finger, preventing any accidental slipping of the hand onto the blade. Some designs feature a second “Flipper” on the opposite side of the blade, forming a small “hilt guard” such as a fixed blade knife has, which can prevent another blade from sliding up into the hilt in combat. These “flippers” are now being found on other brands of knives as well, such as Kershaw, even cheaper knives, including certain versions of Schrade’s Snowblind tactical folders, and numerous others. Penknife, or pen knife, is a British English term for a small folding knife. [1] Today the word penknife is the common British English term for both a pocketknife, which can have single or multiple blades, and for multi-tools, with additional tools incorporated into the design. [2] Originally, penknives were used for thinning and pointing quills (cf pena, Latin for feather) to prepare them for use as dip pens and, later, for repairing or re-pointing the nib. [1] A penknife might also be used to sharpen a pencil, [3] prior to the invention of the pencil sharpener. In the mid-1800s, penknives were necessary to slice the uncut edges of newspapers and books. [4] A penknife did not necessarily have a folding blade, but might resemble a scalpel or chisel by having a short, fixed blade at the end of a long handle. One popular (but incorrect) folk etymology makes an association between the size of a penknife and that of a small ballpoint pen. During the 20th century there has been a proliferation of multi-function knives with assorted blades and gadgets, including; awls, reamers, scissors, nail files, corkscrews, tweezers, toothpicks, and so on. The tradition continues with the incorporation of modern devices such as ballpoint pens, LED torches/flashlights, and USB flash drives. [5] The most famous example of a multi-function penknife is the Swiss Army knife, some versions of which number dozens of functions and are really more of a folding multi-tool, incorporating a blade or two, than a penknife with extras. [5] A larger folding knife, especially one in which the blade locks into place, is often called a claspknife. The penny knife goes all the way back to the 18th century and was a very simple utility knife, originally with a fixed blade. It got the name penny knife because of what it reportedly cost in England and America during the late 18th century: one penny. [1] The famous Fuller’s Penny Knife helped gain the reputation of Sheffield, England, cutlers in the pre-industrial era of the early 18th century. [2] Description The penny knife would later evolve into a extremely basic, mass-produced pocketknife with a folding blade, which pivoted freely in and out of the handle without a backspring or other device to hold it in position (other than the frictional pressures of the knife handle). This type of inexpensive folding knife was quite popular with rural farmers in the United States, England, France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain for much of the 19th and part of the 20th century, and consequently is often called a farmer knife, sodbuster knife, or peasant knife. In modern production, the smallest models of the Opinel, an early 20th-century peasant’s knife, continue to use this basic design, consisting of a folding blade pivoting on an axle mounted through a steel-bolstered wooden handle. Knife collecting is a hobby which includes seeking, locating, acquiring, organizing, cataloging, displaying, storing, and maintaining knives. Some collectors are generalists, accumulating an assortment of different knives. [1] Others focus on a specialized area of interest, perhaps bayonets, knives from a particular factory, Bowie knives, pocketknives, or handmade custom knives. [2] The knives of collectors may be antiques or even marketed as collectible. Antiques are knives at least 100 years old; collectible knives are of a later vintage than antique, and may even be new. Collectors and dealers may use the word vintage to describe older collectibles. Some knives which were once everyday objects may now be collectible since almost all those once produced have been destroyed or discarded, like certain WW2 era knives made with zinc alloy handles which are rapidly degrading due to the material’s shelf life. Some collectors collect only in childhood while others continue to do so throughout their lives and usually modify their collecting goals later in life… History Knives have been collected by individuals since the 19th century with formal collecting organizations beginning in the 1940s. [3] The custom knife-collecting boom began in the late 1960s and continues to the present. [2] Beginning a collection Some novice knife collectors start by purchasing knives that appeal to them, and then slowly work at acquiring knowledge about how to build a collection. [4] In general, knives of significance, artistic beauty, values or interest that are “too young” to be considered antiques, fall into the realm of collectibles. But not all collectibles are limited editions, and many of them have been around for decades. [5] Many knife collectors enjoy making a plan for their collections, combining education and experimentation to develop a personal collecting style, and even those who reject the notion of “planned collecting” can refine their “selection skills” with some background information on the methods of collecting. [6] Strategies Knife magazines such as Knives Illustrated and Blade are one of the most popular means to learn more about the field. Attending knife shows, gun shows, and militaria shows is another way for collectors to familiarize themselves with the hobby. These shows sometimes include seminars on a variety of subjects such as knife making seminars, the history of knife companies, starting a collection or how to insure a collection. There are a number of books dedicated to collecting knives. [7] Although national and international collector clubs exist such as the National Knife Collectors Association. A collector may find and join a local knife club to meet other people who collect knives. Knife publications frequently list the location, date and time of club meetings as a service to new collectors. Collectors who have already narrowed their collecting focus to the knives of a particular maker or factory may want to join a club that focuses on this producer’s work, such as the Randall Knife Society, Emerson’s Collector Club, etc. [8] The Internet A potential collector may wish to chat with other knife collectors in specialized discussion forums via the Internet. Fellow knife collectors are usually very happy to share information with new collectors; this includes information about where they have been successful in acquiring their knives, where they have struggled and what they are looking for. [9] Knife discussion forums There are a number of Usenet and Internet forums dedicated to the discussion of knives and knife collecting. The oldest of such forums is rec. Knives, a Usenet group started in 1992. [9] Manufacturers such as Cold Steel, Spyderco, and Benchmade have established their own forums giving them input from users and a method of responding to customer service issues in a timely fashion. Some forums such as Usual Suspects Network have gone so far as to host their own knife shows on a scale similar to Blade magazine’s annual Blade Show. [10] YouTube and knife collecting A popular resource for new information on knives is YouTube. There are many YouTube knife collectors who can a help a person decide if they want to add a knife to their collection. On YouTube, a person can learn about the blade steel, the ergonomics, the price point as well as a lot of other information that pertains to the knife. Also, a person can add comments to specific videos and get answers to questions about the knife they are looking at. This is another form of communication between knife collectors. Also, some companies post videos showcasing newly released knives. [citation needed] Instagram and knife collecting With the popularity of apps on phones, Instagram emerged as another resources that knife collectors use to get information about knives, as well as follow other knife collectors who post pictures of their knives. Instagram is different from video websites like YouTube because, instead of posting videos, most users post photos of their knives. It is another tool to view knives and learn more about certain aspects of knives. Also, it is a good way of keeping track of new knives being released, as well as the works of custom knife makers. Must be deducted from the retail cost to determine the object’s immediate value on the secondary market, thus, retail cost is not equivalent to secondary market resale value. Depending on several different factors, individuals, auctioneers, and secondary retailers may sell a knife for more, the same, or less than what they originally paid for it. These factors include, but are not limited to, condition, age, supply, and demand. [11] The 1960s through the present were major years for the manufacturing of contemporary collectible knives. A speculative secondary markets developed for many knives in the 1990s. Because so many people bought for investment purposes, duplicates are common. And although many knives were labeled as “limited editions, ” the actual number of items produced was very large. The result of this is that there is very little demand for many (but not all) items produced during this time period, which means their secondary market values are often low. Industry leaders believe that the secondary market is important for several reasons: primarily to allow experienced collectors to upgrade their collections, to stimulate the market and encourage new collectors, and to provide a means for monetary appreciation. To stimulate the market, collectors may obtain some good quality pieces that have been traded in the past. They have an opportunity to learn the history of the hobby by owning some of the knives that have been favorites in the past. Some custom knife makers have large followings of collectors. The secondary market can range anywhere from 50% to 200% of the knife’s original value. Most knife publications offer annual price guides to give collectors an idea of what their knives may be worth. Bonded leather, also called reconstituted leather or blended leather, is a term used for a manufactured upholstery material which contains animal hide. It is made as a layered structure of a fiber or paper backer covered with a layer of shredded leather fibers mixed with natural rubber or a polyurethane binder that is embossed with a leather-like texture. It differs from bicast leather, which is made from solid leather pieces, usually from the split, which are given an artificial coating… Bonded leather is made by shredding leather scraps and leather fiber, then mixing it with bonding materials. The mixture is next extruded onto a cloth or paper backing, and the surface is usually embossed with a leather-like texture or grain. Color and patterning, if any, are a surface treatment that does not penetrate like a dyeing process would. The natural leather fiber content of bonded leather varies. The manufacturing process is somewhat similar to the production of paper. [1] Lower-quality materials may suffer flaking of the surface material in as little as a few years, while better varieties are considered very durable and retain their pattern and color even during commercial use. [1] Because the composition of bonded leathers and related products varies considerably, and is sometimes a trade secret, it may be difficult to predict how a given product will perform over the course of time. There is a wide range in the longevity of bonded leathers and related products; some better-quality bonded leathers are claimed to be superior in durability over low-quality genuine leather. [2] Applications Bonded leather can be found in furniture, bookbinding, and various fashion accessories. Products that are commonly constructed with different varieties of bonded leather include book covers, cases and covers for personal electronics, shoe components, textile and accessory linings, portfolios and briefcases, handbags, belts, chairs, and sofas. [3] A more fragile paper-backed bonded leather is typically used to cover books such as diaries and Bibles, and various types of desk accessories. These bonded leathers might contain a smaller proportion of leather than those used in the furniture industry, and have some leather exposed in the product’s surface, producing the characteristic odor associated with leather. These same applications can alternately use artificial leather constructed in a similar appearance to bonded leather. There is some debate and controversy over the ethics of using the term “bonded leather” to describe an upholstery product, which is actually a reconstituted leather, specifically in the home furnishings industry. A Leather Research Laboratory commented calling a product “bonded leather” is deceptive because it does not represent its true nature. It’s a vinyl, or a polyurethane laminate or a composite, but it’s not leather. [10] In 2011 the European Committee For Standardization published EN 15987:2011’Leather – Terminology – Key definitions for the leather trade’ to stop confusion about bonded leather, according to which the minimum amount of 50% in weight of dry leather is needed to use the term “bonded leather”. The US Federal Trade Commission recommends giving a percentage of leather included. [11] The Federal Trade Commission has said that The guidelines caution against misrepresentations about the leather content in products containing ground, reconstituted, or bonded leather, and state that such products, when they appear to be made of leather, should be accompanied by a disclosure as to the percentage of leather or other fiber content. The guidelines also state that these disclosures should be included in any product advertising that might otherwise mislead consumers as to the composition of the product. A knife (plural knives; from Old Norse knifr’knife, dirk'[1]) is a tool or weapon with a cutting edge or blade, often attached to a handle or hilt. One of the earliest tools used by humanity, knives appeared at least 2.5 million years ago, as evidenced by the Oldowan tools. [2][3] Originally made of wood, bone, and stone (such as flint and obsidian), over the centuries, in step with improvements in both metallurgy and manufacturing, knife blades have been made from copper, bronze, iron, steel, ceramic, and titanium. Most modern knives have either fixed or folding blades; blade patterns and styles vary by maker and country of origin. Knives can serve various purposes. Hunters use a hunting knife, soldiers use the combat knife, scouts, campers, and hikers carry a pocket knife; there are kitchen knives for preparing foods (the chef’s knife, the paring knife, bread knife, cleaver), table knives (butter knives and steak knives), weapons (daggers or switchblades), knives for throwing or juggling, and knives for religious ceremony or display (the kirpan). NKCA HISTORY OF THE KNIVES! IKnife Collector Hosted by Gus Marsh Topic: NKCA (National Knife Collectors Association) March 13, 2013 The National Knife Collectors Association began when a group of collectors, who had been working the gun-shows in Tennessee and Kentucky, turned to knives following the Gun Control Act of 1968. They began to recognize the growing number of knife enthusiasts and held the combined opinion that organizing and promoting the growing trend would expand their new hobby, as well as their own businesses. The economic side of things was not ignored, as the new club was first called the National Knife Collectors & Dealers Association. The first elected president of the new club was the leading knife dealer of the time, James F. The year was 1972, and within two years, the organization had a small newsletter and had signed several hundred members nationwide. In 1974, Parker proposed that the new club knife produce a collector’s knife exclusively for its members as an incentive for membership. He chose an Anglo-Saxon whittler based on the most desirable Case pattern, the 6391 whittlers. Manufactures were interested in producing this small run, so Parker approached Howard Rabin of Star Sales in Knoxville, Tennessee, the U. Importer of German made Kissing Crane knives. Rabin’s company was a major supplier of knives to the emerging knife collectors’ market, and he was eager to make the 1,200 knives that the organization needed. In the brief history one can find about the NKCA, this all sounds like things went smoothly, but the reality is different. When Parker first presented the club knife idea to the NKCA board of directors, one of the board members remarked to a crowd following the meeting: Oh my God, Parker has just bankrupted the Association. The club knife program at the time was an audacious move since the KNCA did not have 1,200 members. Afterwards, numerous collectors said they would have paid more than that had they known that was all it would bring. Thus the beginning of the club knives as a promotional tool and fundraiser for collector organizations began. The record of what followed within the NKCA can best illustrate the initial success of the ventures. The 1976 Club knife, a Case 4380 whittler, with a production of 3,000, would sell out. Five thousand of the 1977 Kissing Crane stag-handled gunboat canoe would be produced, followed by six thousand IXL/Wostenholm green bone handled three blade canoes in 1978. The peak would be reached in 1981, with an issue of 12,000 NKCA club knives, made by Queen. From that high point the NKCA membership declined, as did the number of annual club knives produced. Part of the burnout of investing in club knives came from the massive growth of regional clubs, who each wanted their own club knives for their members. This demand for unique designs soon encompassed all the rare unusual patterns, and a rare vintage pattern that had not been reproduced by a club became almost impossible to find. Many remedies were attempted: changing handle materials, shifting blades around, adding blades to existing patterns, changing the size. But nothing worked as well as the early revival of long discontinued vintage patterns, as originated by Parker and the NKCA. The number of club knives soon made it impossible to collect them all, a goal that many collectors tried when the club knife phenomena began. (Including me) The oversupply stifled grown of value, and in many instances valued fell. A Case bone handled trapper on the resale market is about the same price across the board, no matter if it is a small club making 50 or a large club making 200. Club knives do have their appeal, often unique or resurrected rare designs, popular handle material, and usually etching on the blade that readily identifies the club, the year and the quantity made. The irony is that the knives have rarely captured the enthusiasm of the vintage knife collectors, which was the original market for which the knives were intended. The National Knife Collectors Association and the Club Knife June 10, 2011 tags: Knives, National Knife Collectors Association by beckettedit By J. Bruce Voyles The knife that started it all. This is the original prototype supplied by Kissing Crane to the NKCA for their 1975 club knife. The National Knife Collectors Association began when a group of collectors-who had been working the gun shows in Tennessee and Kentucky-turned to knives following the Gun Control Act of 1968. The year was 1972, and within two years, the organization had a small newsletter and had signed several-hundred members nationwide. In 1974, Parker proposed that the new club produce a collectors knife exclusively for its members as an incentive for membership. He chose an Anglo-Saxon whittler based on the most desirable Case pattern (and the highest collectors-knife value at the time)-the 6391 whittler. Manufacturers were interested in producing this small run, so Parker approached Howard Rabin of Star Sales (Knoxville, Tennessee), the U. Importer of German-made Kissing Crane knives. In the brief history one can find of the NKCA, this all sounds like things went smoothly, but the reality is different. The as-produced version of the 1975 NKC&DA club knife. Etched blade, stamped serial number into the bolsters, NKC&DA shield. The club knife program at the time was an audacious move since the NKCA did not have 1,200 members. Afterward, numerous collectors said they would have paid more than that had they known that was all it would bring. The initial success of the venture can best be illustrated by the record of what followed within the NKCA. The 1976 Club knife, a Case 4380 whittler, with a production of 5000, would sell out. Six thousand of the 1977 Kissing Crane stag-handled gunboat canoe would be produced, followed by Eight thousand IXL/Wostenholm green bone handled three-blade canoes in 1978. Issued when the NKCA club knife program was at its zenith, this four-knife set was produced as a fundraising set for the NKCA Museum. The four manufacturers produced their knives at cost for the NKCA. The profit from this since issue of 2,500 knives paid for the construction of the NKCA Museum in Chattanooga. The plethora of club knives soon made it impossible to collect them all, a goal that many collectors tried when the club knife phenomena began. The oversupply stifled grown of value, and in many instances valued fell. No need to reinvent the wheel, as this selection of Flint River club knives demonstrate how regional clubs followed the NKCA’s lead for producing club knives. A Case bone handled trapper on the resale market at about the same price across the board, no matter if it is a small club making 50 or a large club making 200. Club knives do have their appeal-often unique or resurrected rare designs, popular handle materials, and usually etching on the blade that readily identifies the club, the year, and the quantity made. ” Knife Museum “Dissolved; Collection to 3 New Venues By Steve Shackleford – May 5, 2014 4619 National Knife Museum is dissolved. (Mike Carter image) The National Knife Museum has been dissolved. Its knife inventory will be relocated to three new locations. (Mike Carter image) After over 30 years of operation, the National Knife Museum (NKM) is being dissolved. However, the old museum’s knife inventory will carry on at three separate museums, according to Lisa Sebenick, president of the National Knife Collectors Association (NKCA) and secretary of the NKM. The only museum of its kind in the USA, the NKM had been housed on the mezzanine of Smoky Mountain Knife Works in Sevierville, Tennessee, since late 2006. “The officers, directors and staff of the National Knife Museum sincerely thank Smoky Mountain Knife Works/Kevin Pipes for giving our collection of cutlery a home these past seven years, ” an NKM release stated. National Knife Museum is dissolved. (Mike Carter image) The National Knife Museum is being dissolved. (Mike Carter image) According to Sebenick, the museum’s knife inventory will be donated to three different museums: the National Rifle Association Museum in Springfield, Missouri, the Berman Museum of World History in Anniston, Alabama, and the Janney Furnace Museum in Ohatchee, Alabama. As for the 50 or so Bill Moran knives that were exhibited at the NKM, an official statement from the Moran Foundation was that no decision had been made for those knives at press time. At some future date, perhaps some of the Moran knives would be put on loan elsewhere, the statement concluded. Located in Chattanooga, Tennessee, the original museum was built in 1981 and was the creation of the NKCA as a separate, educational, non-profit corporation. It opened its doors in 1982. It was moved to Sevierville in 2006. According to Pete Cohan in BLADE’s Guide to Knives & Their Values, 7th Edition, while many NKCA members were heavily involved in the original museum’s creation, it was the donation of three major individual knife collections-those of Cutlery Hall-Of-Famer Frank Forsyth, Dr. James Wilkison and Dr. William Rosenthal-that created the foundation for a comprehensive museum display collection. During its run at Smoky and in addition to the many other knives it exhibited, the NKM also included the custom knife collection of Cutlery Hall-Of-Famer Joe Drouin, a number of club knives from knife clubs around the country, various knife ephemera and more. Velour or velours is a plush, knitted fabric or textile similar to velvet or velveteen. It is usually made from cotton, but can also be made from synthetic materials such as polyester. Velour is used in a wide variety of applications, including clothing and upholstery. [1] Velour can also refer to a rough natural leather sometimes called velour leather. Chrome tanned leather is ground from the inside, which forms a delicate, soft layer on the surface. It is used for footwear, clothing, and upholstery. This type of leather is often confused with velvet suede and chamois… Uses Velour can be a woven or a knitted fabric, allowing it to stretch. It combines the stretchy properties of knits with the rich appearance and feel of velvet. Velour is used in dance wear for the ease of movement it affords, and is also popular for warm, colorful, casual clothing. When used as upholstery, velour often is substituted for velvet. The velour widely used in the manufacture of theater drapes and stage curtains is manufactured using the same weaving process as velvet: two sets of warps and wefts woven at the same time, with additional threads that will become the nap in between, then cut apart to produce the two separate tufted fabrics. Cotton velours used for this range from 16oz per linear yard to 32oz per linear yard, synthetic versions typically run 13oz to 32oz per linear yard. Velour also has uses in the cleaning industry, most notably on vacuum attachments to help capture debris. Artificial leather, also called synthetic leather, is a material intended to substitute for leather in upholstery, clothing, footwear, and other uses where a leather-like finish is desired but the actual material is cost prohibitive or unsuitable. Artificial leather is known under many names, including leatherette, imitation leather, faux leather, vegan leather, PU leather, and pleather… Manufacture Steps to make synthetic polyurethane leather: The base fabric A polyurethane coating is applied A color coat is added A textured finish is added[2] Many different methods for the manufacture of imitation leathers have been developed. One of the earliest was Presstoff. Invented in 19th century Germany, it was made of specially layered and treated paper pulp. It gained its widest use in Germany during the Second World War in place of leather, which under wartime conditions was rationed. Presstoff could be used in almost every application normally filled by leather, excepting items like footwear that were repeatedly subjected to flex wear or moisture. Under these conditions, Presstoff tends to delaminate and lose cohesion. Another early example was Rexine, a leathercloth fabric produced in the United Kingdom by Rexine Ltd of Hyde, near Manchester. It was made of cloth surfaced with a mixture of nitrocellulose, camphor oil, alcohol, and pigment, embossed to look like leather. It was used as a bookbinding material and upholstery covering, especially for the interiors of motor vehicles and the interiors of railway carriages produced by British manufacturers beginning in the 1920s, its cost being around a quarter that of leather. [3] Poromerics are made from a plastic coating (usually a polyurethane) on a fibrous base layer (typically a polyester). The term poromeric was coined by DuPont as a derivative of the terms porous and polymeric. The first poromeric material was DuPont’s Corfam, introduced in 1963 at the Chicago Shoe Show. Corfam was the centerpiece of the DuPont pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair in New York City. Leatherette is also made by covering a fabric base with a plastic. The fabric can be made of natural or synthetic fiber which is then covered with a soft polyvinyl chloride (PVC) layer. Leatherette is used in bookbinding and was common on the casings of 20th century cameras. Cork leather is a natural-fiber alternative made from the bark of cork oak trees that has been compressed, similar to Presstoff. A fermentation method of making collagen, the main chemical in real leather, is under development. [4] Environmental effect The production of the PVC used in the production of many artificial leathers requires a plasticizer called a phthalate to make it flexible and soft. PVC requires petroleum and large amounts of energy thus making it reliant on fossil fuels. During the production process carcinogenic byproducts, dioxins, are produced which are toxic to humans and animals. [5] Dioxins remain in the environment long after PVC is manufactured. When PVC ends up in a landfill it does not decompose like genuine leather and can release dangerous chemicals into the water and soil. [citation needed] Polyurethane is currently more popular for use than PVC. [6] The production of some artificial leathers requires plastic, with others only requiring plant-based materials; the inclusion of artificial materials in the production of artificial leathers notably raises sustainability issues. [7] However, some reports state that the manufacture of artificial leather is still more sustainable than that of real leather, with the Environmental Profit & Loss, a sustainability report developed in 2018 by Kering, stating that the impact of vegan-leather production can be up to a third lower than real leather. [7] Clothing and fabric uses Artificial leathers are often used in clothing fabrics, furniture upholstery, and automotive uses. [8] One disadvantage of plastic-coated artificial leather is that it is not porous and does not allow air to pass through, allowing sweat to accumulate if it is used for items that will be in continuous contact with a person’s body, such as clothing and car seat coverings. One of its primary advantages, especially in cars, is that it requires little maintenance in comparison to leather, and does not crack or fade easily, though the surface of some artificial leathers may rub and wear off with time. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Knives, Swords & Blades\Blade Parts, Supplies & Accs\Boxes, Cases & Pouches”. The seller is “sidewaysstairsco” and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Norway, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay.

- Brand: NKCA

- Type: Cases & Boxes

- Color: Black

- Original/Reproduction: Original

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States